Produced on the occasion of Modell und Ruine, Dessau, 2019. For Haris Epaminonda’s installation inside the Meisterhaus Feininger in Dessau, six individual recordings are compiled into a single track. For each recording, a microphone was positioned on a window sill, documenting the interweaving sounds of the interior and exterior spaces.

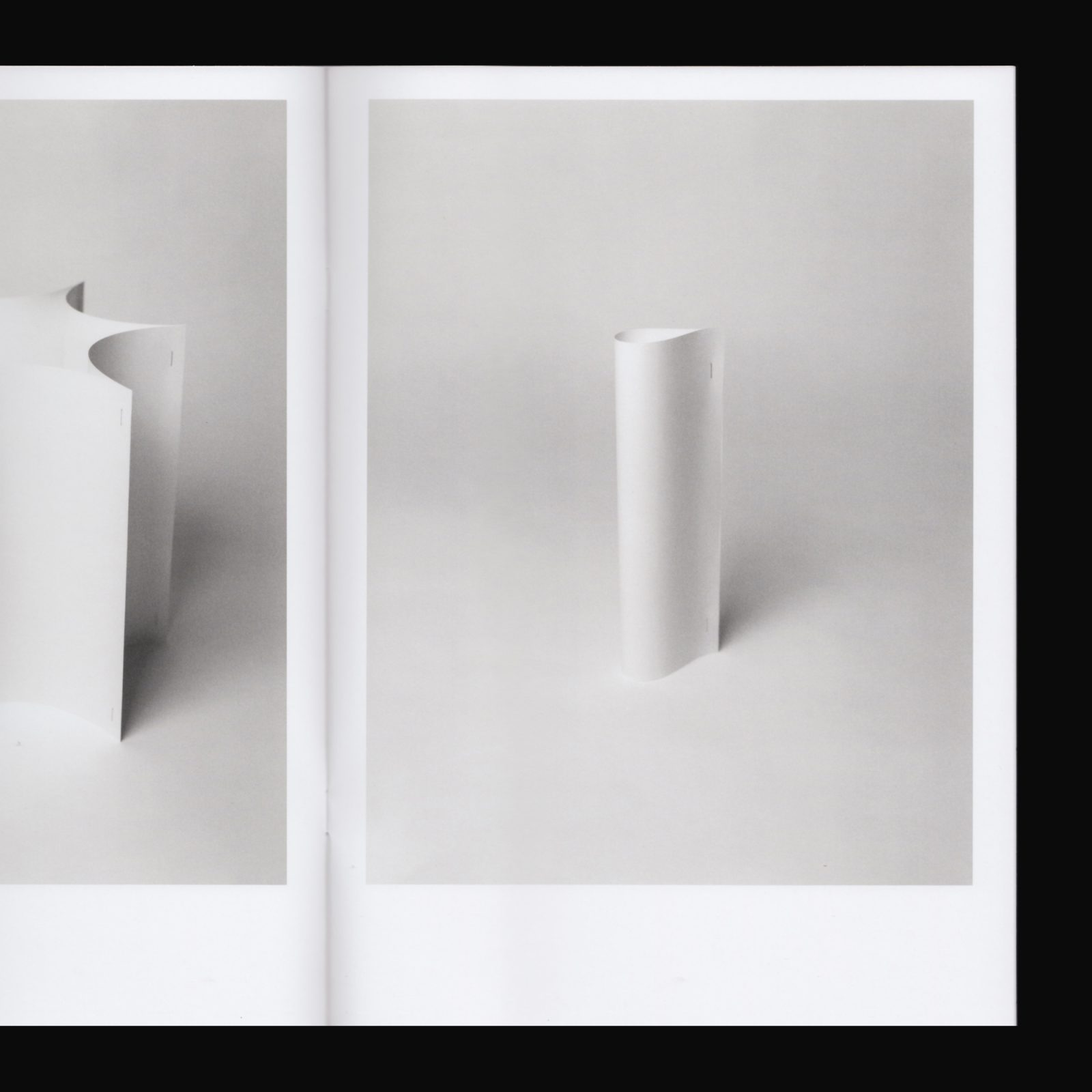

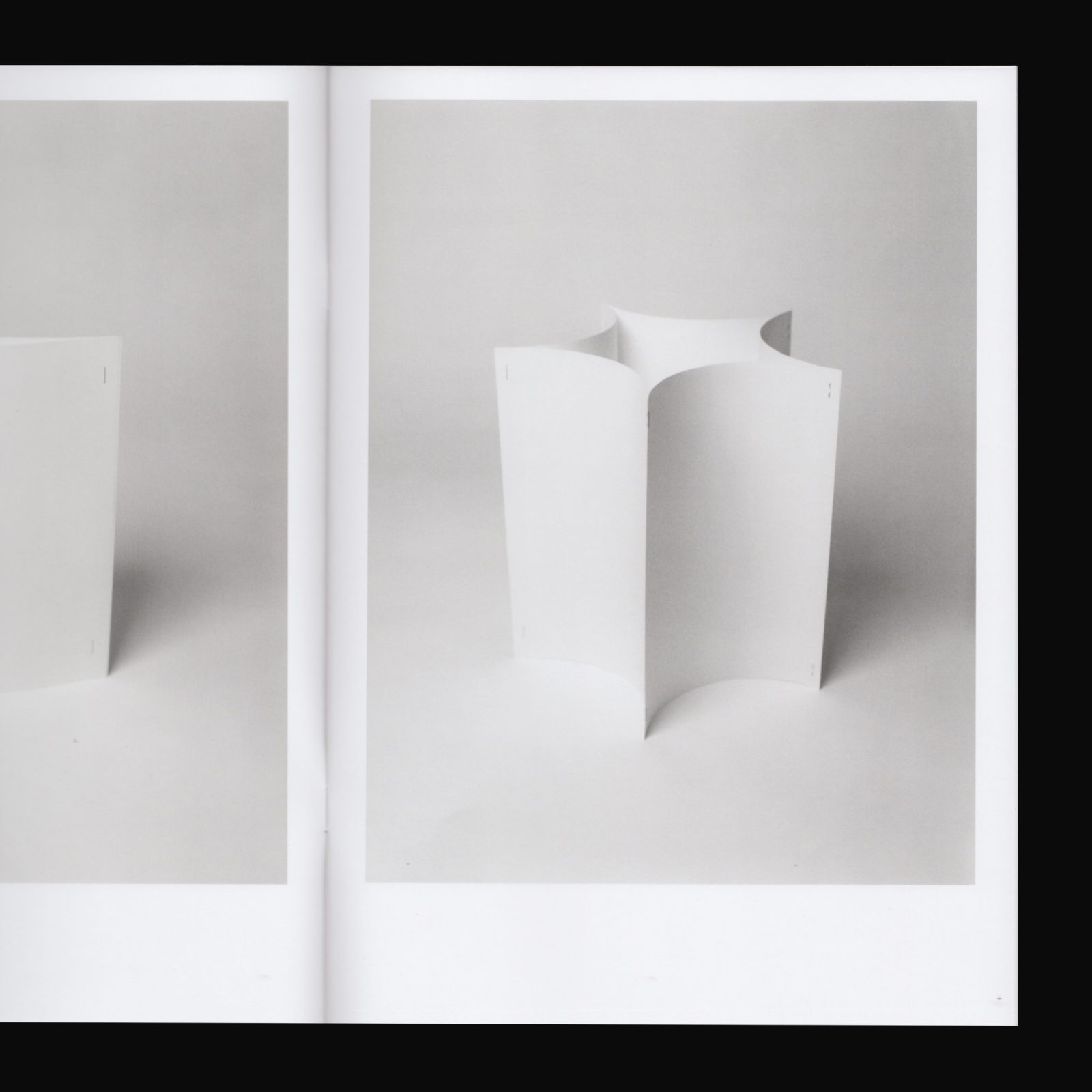

Old Tjikko is a 9,550 year-old Norway Spruce, located on Fulufjället Mountain of Dalarna province in Sweden. Old Tjikko originally gained fame as the “world’s oldest tree”. Leif Kullman (Professor of Physical Geography at Umeå University who discovered Old Tjikko), attributed this growth spurt to global warming and gave the tree its nickname “Old Tjikko” after his late dog.This publication acts as a memorial of sorts to the original Tjikko. Printed in an edition of 25.

Quora is a question-and-answer website where questions are asked, answered, edited, and organized by its community of users in the form of opinions. On March 6, 2012, a question was placed anonymously.. The replies have been listed here in chronological order

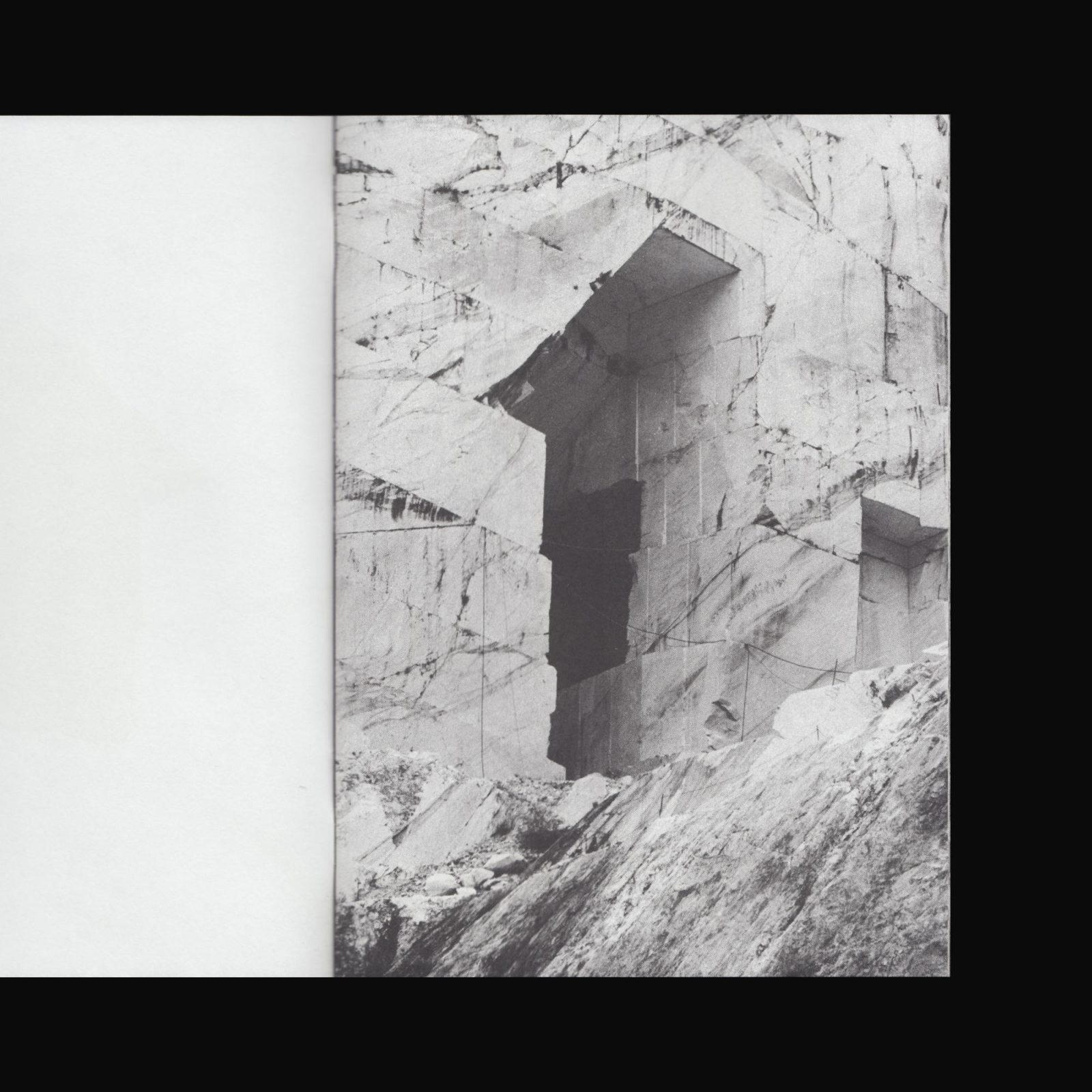

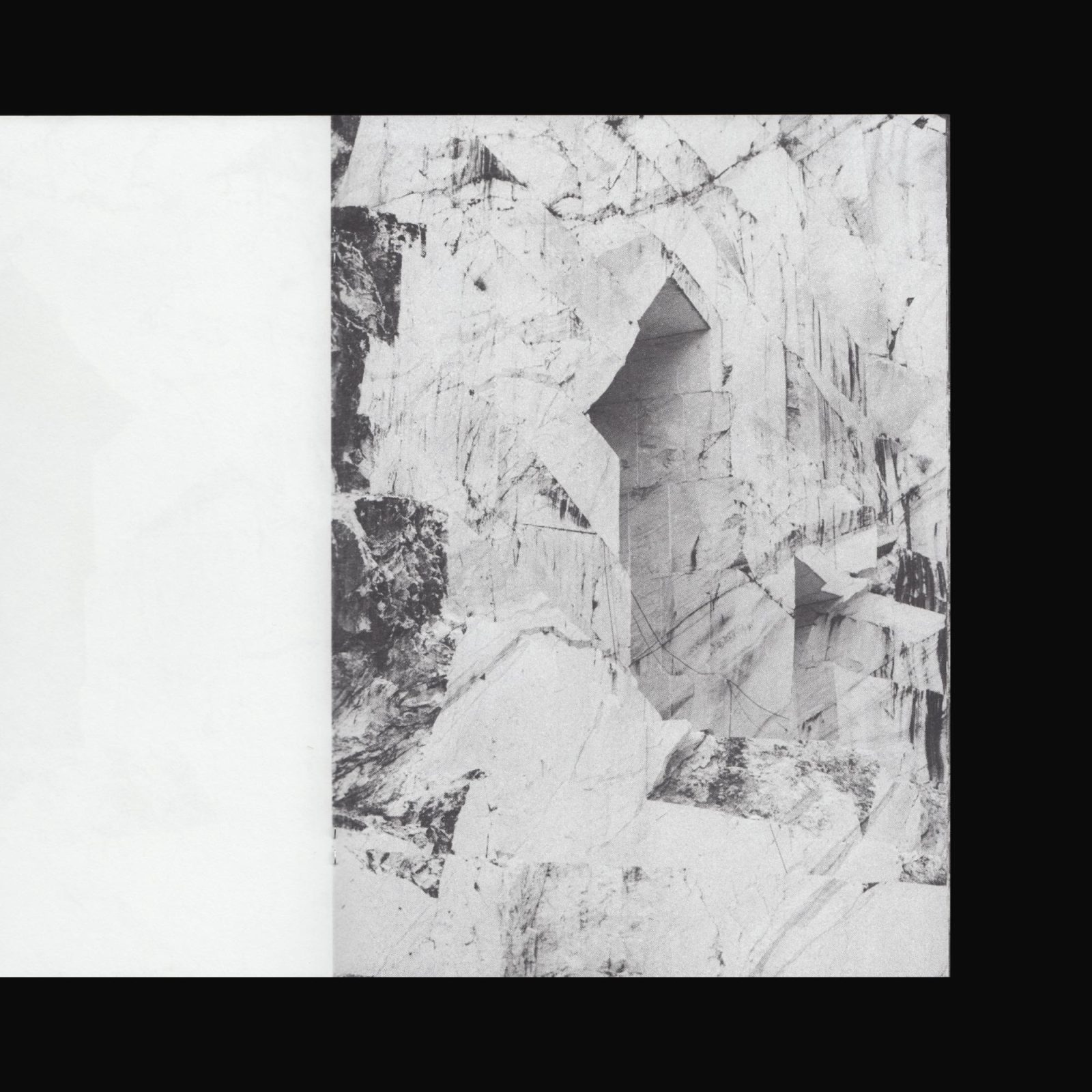

Riso printed booklet of photos taken near Carrara, edition of 100.